Introduction:

Modernism does not announce itself politely. It enters academic study as a disturbance an idea that refuses to stay still. When one first encounters the term modernism, it appears everywhere and nowhere at once: in novels that abandon plot, in paintings that refuse perspective, in music that sounds deliberately unsettling. The immediate question, then, is not what is Modernism? but why does it feel so difficult to define?

This difficulty is not a failure of scholarship; it is the very condition Modernism responds to. To understand Modernism is to retrace an intellectual journey one that moves through reading, looking, listening, questioning, and gradual recognition. What follows is not a fixed definition, but an account of how Modernism begins to make sense when approached patiently, historically, and critically.

What Is Modernism?

At first glance, Modernism is often described as a literary or artistic movement that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet such definitions quickly feel insufficient. As one reads critical essays by scholars like Raymond Williams or Malcolm Bradbury, it becomes clear that Modernism is not merely a collection of stylistic experiments. It is better understood as a response to a crisis of meaning.

Modernism emerges when writers and artists begin to doubt whether traditional forms religious belief, realist narration, moral certainty, or Enlightenment rationality are still capable of explaining human experience. The modern world, shaped by industrialization, urban life, and scientific thinking, no longer feels coherent or stable. Modernism does not attempt to restore lost unity; instead, it confronts fragmentation directly.

In this sense, Modernism is not defined by what it claims to know, but by what it refuses to pretend it knows.

How Did Modernism Begin? History Pressing into Art:

Modernism begins at the moment when artists and writers realize that the old ways of telling the truth have stopped working. It does not announce itself with a date or a declaration. Instead, it arrives quietly, through discomfort through the sense that familiar forms no longer match lived experience.

By the late nineteenth century, everyday life had already begun to feel unstable. Industrialization reorganized time and labor, turning human rhythms into mechanical routines. Cities expanded rapidly, producing anonymity rather than community. People lived surrounded by crowds, yet felt increasingly alone. The world was moving faster, but meaning did not move with it.

At the same time, intellectual certainty was eroding. Scientific and psychological theories unsettled religious belief and moral assurance. Human beings were no longer understood as coherent, rational selves, but as divided subjects shaped by instinct, memory, and unconscious desire. Reality itself began to feel fractured partial, subjective, unreliable.

Then came the First World War, and with it a shock so severe that it transformed unease into rupture. The war did not simply destroy lives; it destroyed faith. Mechanized slaughter revealed that modern progress was capable of producing devastation on an unimaginable scale. The language of heroism, national pride, and moral purpose sounded obscene beside the reality of trenches, gas, and mass death. After the war, artists could no longer believe in continuity historical, moral, or aesthetic. The forms inherited from the nineteenth century felt dishonest because they implied order where none seemed to exist. To write as if the world were stable was to lie.

Modernism emerges at this point of crisis. It is not rebellion for novelty’s sake, but a struggle for sincerity. Fragmentation, experimentation, and difficulty are not stylistic games; they are attempts to register a broken reality. Modernist art accepts uncertainty, dislocation, and silence because these reflect the conditions of modern life itself. In this sense, Modernism begins when history forces art to change not because artists wanted to be radical, but because they could no longer pretend that the world made sense.

Learning to See Modernism: Events and Images as Historical Clues

Modernism becomes most legible when it is encountered visually when history is seen rather than summarized. Long before writers theorized fragmentation and disillusionment, these conditions were already visible in the material world. Images of factory interiors, for instance, reveal a radical reordering of life. Human bodies appear subordinated to machines, arranged along assembly lines where time is measured mechanically rather than organically. The rhythm of labor no longer follows natural cycles but the relentless pace of industrial production. Such images expose a modern world in which individuality is diminished, and human experience is standardized.

The visual record of the First World War intensifies this sense of rupture. Photographs of trench warfare show landscapes torn apart, bodies indistinguishable from mud and machinery. Soldiers appear as anonymous figures, reduced to uniforms and numbers. These images refuse the romantic language of heroism that had once accompanied war. Instead, they confront viewers with mass death, mechanized violence, and the erasure of personal identity. It is within this visual reality that modernist literature’s themes of fragmentation, silence, and despair take root.

Modernism’s visual logic is equally apparent in the radical transformations of art. Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) represents a decisive break from centuries of Western aesthetic tradition. The painting abandons linear perspective, anatomical harmony, and idealized beauty. Instead, bodies are fractured into angular planes, faces resemble masks, and the viewer is confronted rather than invited. Perception itself becomes unstable. Picasso does not represent reality as it appears; he represents reality as it feels in a fractured modern world.

This refusal of coherence mirrors the modernist belief that traditional forms no longer tell the truth. The painting demands that the viewer participate actively, reconstructing meaning from disjointed elements much like a reader navigating a modernist text.

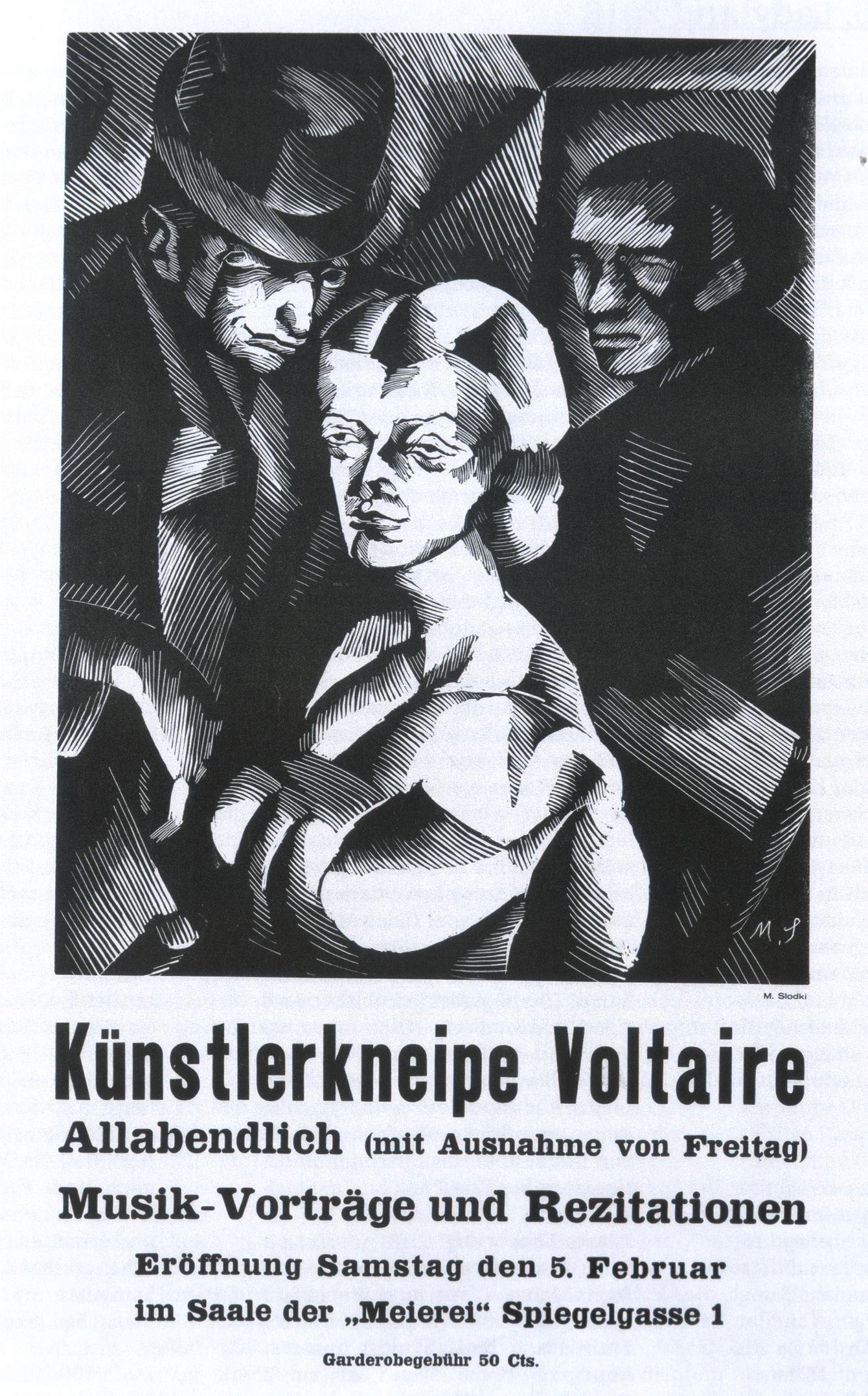

An even more radical response appears in Dada, particularly in the performances at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich during the war years. Dada artists staged chaotic readings, nonsensical poetry, and absurd performances that deliberately rejected meaning, logic, and aesthetic beauty. This was not playfulness, but protest. For artists who had witnessed a civilization capable of industrialized slaughter, coherence itself appeared suspect. If rational systems had led to war, then irrationality became a form of resistance.

Dada’s visual and performative chaos exposes a key modernist insight: that meaning is not guaranteed, and that art must sometimes reflect breakdown rather than order.

Seen through these images and events, Modernism no longer appears merely as a literary or artistic movement. It emerges as a historical consciousness shaped by shock, speed, and disintegration. Fragmentation, abstraction, and difficulty are not stylistic preferences; they are responses to a world that has lost its coherence. To learn Modernism, then, is to learn how to see history written into form how images, like texts, register the pressure of modern life.

Encountering Modernism Through Reading and Watching:

As engagement with Modernism expands beyond critical texts into lectures, documentaries, archival recordings, and filmed performances, a recurring pattern begins to emerge: Modernism repeatedly unsettles its audience. This disturbance is not accidental, nor is it a by-product of obscurity. Rather, it is a deliberate aesthetic strategy rooted in the historical conditions that produced the movement.

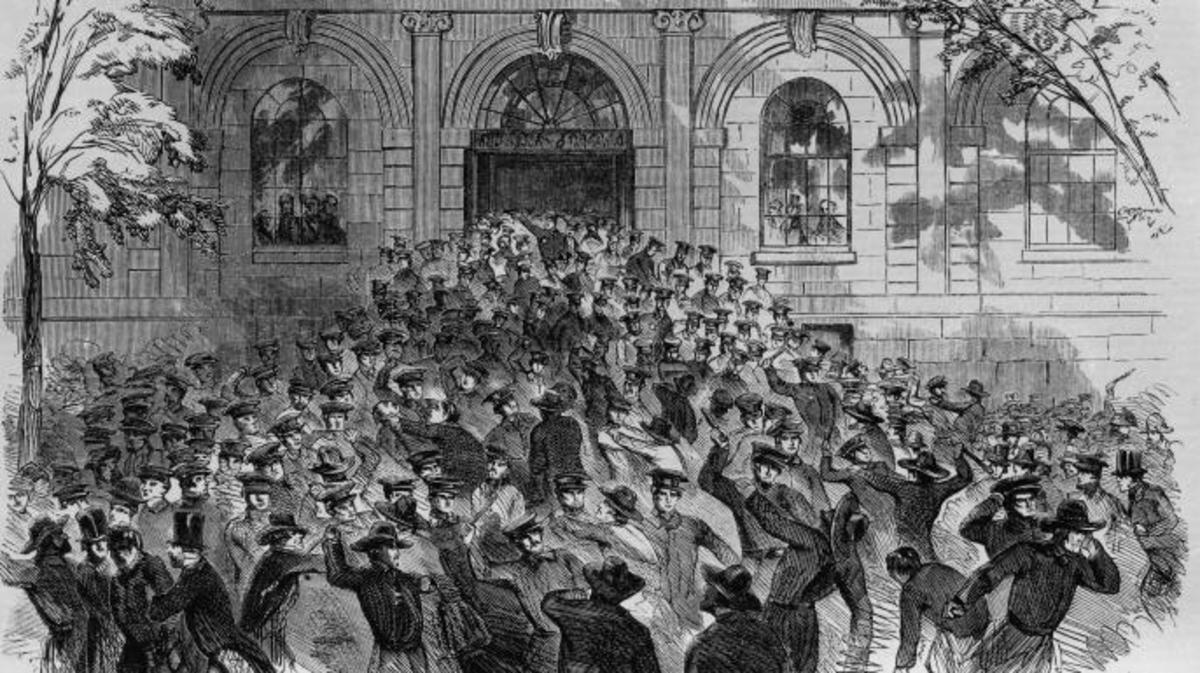

A defining moment often cited in this context is the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913) in Paris. The audience reaction ranging from shouting and mockery to physical altercations has frequently been dismissed as a failure of public taste or understanding. Yet such explanations miss the point. The uproar occurred precisely because the work was understood too clearly as a threat. Stravinsky’s violent rhythms, dissonant harmonies, and rejection of classical musical structure shattered long-held assumptions about beauty, balance, and cultural continuity. What the audience encountered was not simply a new composition, but a world in which familiar systems of order no longer applied.

This moment reveals a fundamental principle of Modernism: it resists passive reception. Modernist works do not offer comfort, clarity, or moral reassurance. Instead, they impose difficulty. They interrupt habitual ways of seeing, hearing, and reading, compelling the audience to confront uncertainty. Meaning is no longer delivered fully formed; it must be actively constructed.

The same demand confronts readers of modernist literature. When encountering the fragmented narration of T. S. Eliot, the interior monologues of Virginia Woolf, or the syntactic experiments of James Joyce, the reader is denied the stabilizing frameworks of linear plot and authoritative voice. This difficulty is not elitism, but epistemological honesty. Modernism assumes that in a world fractured by war, industrialization, and ideological collapse, art that pretends to coherence would be fundamentally dishonest.

Thus, Modernism transforms the role of the audience. The reader, listener, or viewer becomes a collaborator in the production of meaning, navigating ambiguity rather than resolving it. Discomfort, confusion, and resistance are not failures of interpretation; they are evidence that Modernism is functioning as intended.

To encounter Modernism through reading and watching, then, is to experience history pressing directly into form. The shock registered by early audiences is the same shock that modern readers inherit not as a relic of the past, but as a continuing challenge to how meaning, art, and truth are understood.

Characteristics of Modernism:

Modernism cannot be understood as a fixed style or a set of artistic rules. It develops out of a historical moment when earlier ways of understanding the world no longer felt convincing. Religious belief, moral certainty, linear history, and realistic representation had once provided stability, but by the early twentieth century, these structures appeared fragile or broken. The characteristics of Modernism grow directly out of this loss of confidence. They are not aesthetic decorations; they are responses to lived historical uncertainty.

1. Fragmentation and Discontinuity:

Fragmentation is one of the most fundamental characteristics of Modernism. Modernist writers and artists no longer present experience as unified or continuous. Narratives break apart, time shifts suddenly, and perspectives change without warning. This formal disruption reflects how modern life itself is experienced—as interrupted, unstable, and often incoherent.

The growth of industrial cities, the speed of technological change, and the trauma of war made it difficult to believe in smooth progress or orderly development. Fragmentation therefore becomes a truthful form. Rather than forcing experience into a false unity, Modernism allows brokenness to remain visible. What appears difficult or disjointed is, in fact, an attempt to represent reality honestly.

2. Emphasis on Subjective Experience:

Modernism marks a decisive movement away from objective description toward subjective perception. Instead of assuming that reality exists independently and can be described neutrally, Modernists focus on how reality is experienced by the individual mind. Thoughts, memories, emotions, and sensations become central.

This shift is especially clear in modernist literature, where time often follows consciousness rather than chronology. A single moment can contain layers of memory, while years may pass in a sentence. Reality is no longer defined by external events but by internal awareness. This emphasis reflects the modern understanding that truth is not universal or stable, but personal, partial, and constantly shifting.

3. Rejection of Traditional Forms:

Modernists deliberately move away from traditional artistic forms because those forms no longer seem capable of expressing modern experience. Linear plots, clear moral lessons, fixed genres, and harmonious structures belong to a world that assumed order and meaning. For Modernists, continuing to use those forms would be intellectually dishonest.

This rejection is not a rejection of art itself. It is a rejection of inherited conventions that no longer work. Modernist artists dismantle old forms in order to discover new ones forms flexible enough to hold uncertainty, contradiction, and complexity. Innovation becomes necessary, not fashionable.

4. Formal Experimentation:

Because traditional forms feel inadequate, Modernism is marked by intense experimentation. Writers experiment with language and narrative structure; painters experiment with perspective and form; composers experiment with harmony and rhythm. This experimentation is not random. It emerges from the belief that form shapes meaning.

Modernists understand that how something is expressed determines what can be expressed. To represent a fragmented world, form itself must be fragmented. Experimentation becomes a way of thinking through form, testing what art can still do under modern conditions.

5. Ambiguity and Open Meaning:

Modernist works often resist clear interpretation. They do not explain themselves fully, nor do they offer definite conclusions. This ambiguity reflects the collapse of absolute truths in the modern world. When religious, moral, and philosophical certainties no longer command belief, art can no longer pretend to provide final answers.

Instead of guiding the reader toward a single meaning, Modernist works demand active engagement. Meaning is produced through interpretation rather than delivered ready-made. Confusion, uncertainty, and difficulty are not failures; they are part of the experience Modernism creates.

6. Alienation and Isolation:

A strong sense of alienation runs through Modernist writing and art. Individuals appear disconnected from society, tradition, and even from their own sense of self. Modern cities are crowded but lonely; social relationships feel unstable; communication breaks down.

This alienation reflects structural changes in modern life. Industrial labor, bureaucratic systems, and urban anonymity weaken older forms of community and belonging. Modernism does not attempt to resolve this condition. It records it honestly, allowing discomfort and estrangement to remain visible.

7. Crisis of Meaning and Faith:

Modernism develops in the shadow of a profound crisis of belief. Scientific discovery challenges religious explanations of the world, while historical catastrophes especially war undermine faith in progress and moral order. As a result, Modernist works often express doubt, anxiety, or silence rather than confidence.

Even when religious imagery appears, it is often fragmented or unresolved. Meaning is sought, but no longer guaranteed. Modernism captures the tension of living in a world where belief has not disappeared, but certainty has.

8. Self-Awareness of Art:

Modernist art frequently draws attention to its own construction. Rather than pretending to be a transparent reflection of reality, it reminds the reader or viewer that it is an artistic creation. Narrators interrupt themselves, structures reveal their artificiality, and form becomes visible.

This self-awareness prevents passive consumption. It encourages reflection on how meaning is produced and how representation works. Art becomes not an illusion of reality, but a space for questioning reality itself.

9. Reworking the Past:

Although Modernism is often associated with rupture, it remains deeply engaged with the past. Myths, classical texts, and earlier artistic forms reappear in modernist works, but they are altered, fragmented, or placed in new contexts.

The past is not accepted as authority, nor is it simply rejected. It is examined critically. This tension between inheritance and revision lies at the heart of Modernist thinking.

Major Modernists:

Seeing the Historical Pressure Behind the Texts

Modernism becomes most intelligible when its major figures are placed back into the historical environments they inhabited. Woolf, Eliot, and Joyce were not inventing difficulty for its own sake; they were responding to a world visibly altered by industrialization, war, urban crowding, and the collapse of inherited belief systems. To understand their work, one must first learn to see the pressures shaping their perception.

The World They Inherited: Rupture Made Visible

By the early twentieth century, Europe no longer resembled the stable cultural landscape assumed by nineteenth-century realism. Cities expanded rapidly, machines reorganized labor, and the First World War shattered confidence in progress and reason. Modernist writers absorbed this visual and psychological reality before they transformed it into form.

These images clarify why coherence felt dishonest. The world appeared crowded, mechanized, fractured, and overwhelmed by forces beyond individual control. Modernism begins here not in theory, but in historical perception.

Virginia Woolf:

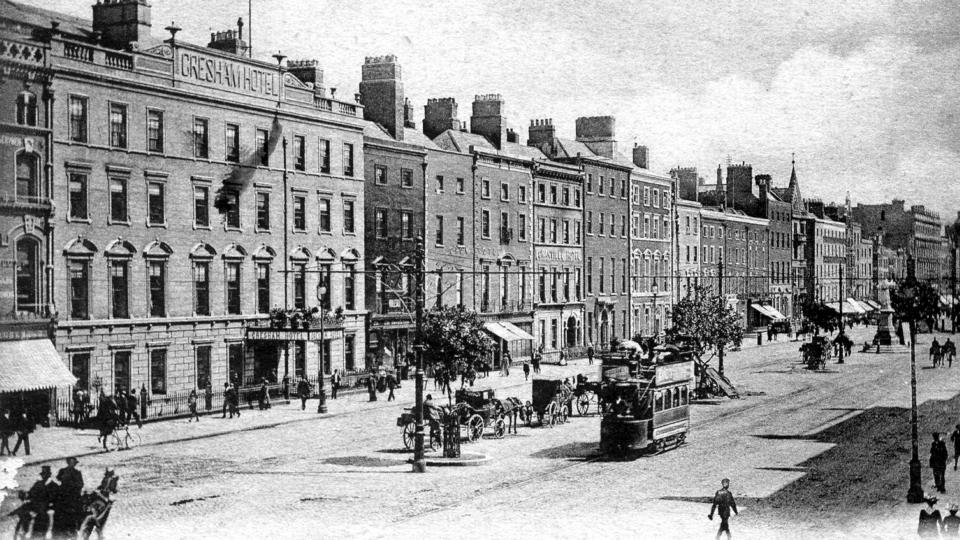

Virginia Woolf’s focus on inner life gains clarity when viewed against the public spaces of modern London. The city Woolf walked through daily was dense, noisy, and socially stratified. External order masked inner vulnerability.

In Mrs Dalloway, Woolf’s characters move through crowds while remaining inwardly isolated. Her turn toward stream of consciousness reflects a conviction that truth now resides in private perception rather than public narrative. Psychological time replaces historical time because the modern subject experiences reality discontinuously.

T. S. Eliot:

Eliot’s The Waste Land emerges directly from a post-war landscape of ruin and exhaustion. His poetic method mirrors the way modern culture appears when viewed honestly: broken, layered, and haunted by fragments of the past.

Eliot’s reliance on quotation and allusion resembles walking through a ruined city where remnants of past civilizations lie scattered. Tradition is no longer whole; it must be pieced together from debris. Fragmentation becomes not an aesthetic preference but a historical condition.

James Joyce:

Joyce’s Dublin is not symbolic abstraction but lived urban reality. His Modernism grows from meticulous attention to ordinary movement streets, shops, bodies, routines.

By representing a single day in Ulysses, Joyce reveals how modern consciousness is shaped by repetition, memory, language, and environment. The extraordinary formal experimentation reflects the pressure placed on language by modern life itself.

Beyond Literature:

Modernism’s visual and performative dimensions expose the same recognition found in Woolf, Eliot, and Joyce: the old structures no longer hold.

Dada’s chaos, Cubism’s fractured perspective, and Stravinsky’s violent rhythms all register a civilization in crisis. These works do not seek harmony; they expose rupture.

Seeing Modernism Clearly

When encountered through events, spaces, and historical images, Modernism appears not as an abstract literary movement but as a mode of survival. Writers and artists were attempting to remain truthful in a world where continuity had been broken where meaning could no longer be inherited, only constructed.

Modernism, then, is not simply a style. It is the visible trace of history pressing into consciousness, forcing new forms into existence.

How Modernists Used (and Often Avoided) the Term “Modernism”

One of the striking paradoxes of Modernism is that many of its central figures did not consistently describe themselves as modernists at all. The term gained currency largely through critics, historians, and later academic frameworks attempting to organize a wide range of artistic responses into a coherent narrative. For the writers and artists themselves, labels were secondary often distrusted because they risked simplifying experiences that felt complex, unstable, and unresolved.

When Modernist figures reflected on their own work, they spoke less about belonging to a movement and more about truthfulness, difficulty, sincerity, and formal necessity. Virginia Woolf, for instance, framed her innovations as attempts to capture life more honestly. T. S. Eliot resisted being understood as merely “new,” emphasizing instead the writer’s ethical responsibility to history. James Joyce rarely theorized Modernism directly; his concern lay in exhausting the possibilities of language itself. What unites these positions is a shared suspicion of fixed categories.

Modernism, then, is best understood not as a self-declared program but as a retrospective name given to a condition of thought. It describes what happens when artists confront a world marked by rupture when inherited explanations no longer persuade, and form itself must be questioned. The term gathers together diverse responses to doubt, historical pressure, and epistemological uncertainty, even though those responses often resisted being gathered at all.

Conclusion:

Modernism is not something one grasps immediately. It is learned gradually through sustained reading, attentive viewing, repeated questioning, and reflective return. Its fragmented structures, subjective focus, and experimental techniques are not aesthetic indulgences or intellectual games. They are serious attempts to think truthfully in conditions where certainty has collapsed.

To understand Modernism is to understand what happens when art can no longer rely on inherited forms, stable meanings, or shared beliefs. It is the moment when representation becomes self-conscious, when difficulty becomes unavoidable, and when the act of making meaning is exposed as fragile and provisional.

In this sense, Modernism does not belong exclusively to the early twentieth century. Wherever the world feels unstable, wherever established answers lose credibility, and wherever artists are forced to begin again without guarantees, the Modernist impulse persists. Modernism continues to speak not as a historical style, but as an ongoing challenge to think, perceive, and create honestly in uncertain times.

No comments:

Post a Comment